INTRODUCTION

In Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province (江西省, 景德鎮), a paint brush rest (Figures 1 - 6) was found at some point in the 20th century. This is one of many identical brush rests found in the area, but these items are remarkably unique from most popular pieces of blue-and-white porcelain: different in use, form, and style than typical blue-and-white pieces seen in the art market today and popular in contemporary media, but also potentially the most potent and reflective of blue-and-white’s beginnings as a medium and its historical significance.

This paper will be focusing on the visual manifestation of cultural exchange in this brush rest. Following the theories of Alfred Gell, Nassos Papalexandrou, and influenced by Bonnie Cheng, the formal qualities of this item will be dissected and contextualized, acknowledging the complexities of China’s history, especially in a time when the dynasties (even those not led by the Han Chinese, the majority ethnic group throughout most of Chinese history) are often presently considered to be strictly of Chinese history and rarely consider the implications of the intersections of different cultural groups that are very palpably present in that history. These external cultural impacts are manifested in this brush rest, and this paper will be highlighting the nuances of this very tangible, very real object as a reminder of the complexities of any nation’s history.

To start, the mere existence of a white porcelain item, such as the one that is the subject of this paper, with cobalt blue painted and glazed onto it is already revealing of a multitude of intersecting cultural groups with different values and beliefs. Up until recent years, blue-and-white porcelain (青花) was believed to not have been first created until the Yuan Dynasty. This, however, was found to be untrue, considering that shards of blue-and-white porcelain had been found recently that were compositionally dated to the Tang and Song dynasties.[1] Those blue-and-white Tang/Song ceramics had been created but destroyed, with only shards remaining, leaving a question as to what prevented the acceleration of the medium during those former dynasties.

Often throughout Chinese history, local gazetteers described the locations of specific reject pits for the disposal of unwanted ceramic pieces, alongside descriptions of new commissions created for local and regional authorities,[2] and therefore, the decision to dismiss entire pieces due to a change in trends, led by the tastes of political authorities was not unfamiliar. During the writing of the Essential Criteria of Antiques, the first major book on Chinese art connoisseurship, written by Cao Zhao in 1388, Jingdezhen hadn’t achieved the status that it would later, and the blue-and-whites were described as gaudy and unsophisticated.[3] It was only during the Yuan dynasty when blue-and-white began to reach higher status as a medium.

MONGOL CHANGES

The Yuan dynasty began with the Mongol takeover of Hangzhou, the Song capital of China. Kublai Khan, the grandson of Ghengis Khan, proclaimed himself emperor of China in the traditional Chinese style, and the Yuan dynasty officially began in 1271.

The Mongols helped foster beneficial market conditions for the spread of blue-and-white ceramics,[4] destigmatizing the role of merchants and shipmakers. According to traditional Confuscian beliefs, those driven by materialism were viewed poorly, and this incentivized the import and export of goods from China, but under Mongol rule, this was overturned,[5] and an official Porcelain Bureau (瓷局) was established to organize and regulate manufacture by the Yuan dynasty.[6] This streamlined manufacturing process was one of the necessary milestones in order for Chinese porcelain as a medium (not exclusively blue-and-white) to reach the status that it eventually would claim, providing the infrastructure to maintain the process of product manufacture and distribution in China. Considering the dismissal of Confuscian beliefs necessary for this sort of development, the role of external cultural forces here is clear. The Mongol leadership even specifically streamlined the production of porcelain to the Kilns of Jingdezhen due to its access to kaolin, the material needed for porcelain production, with the Capital demanding the increased production of blue-and-white pieces for export and imperial use, respectfully.

But why the sudden interest in blue-and-white porcelain when, in the past, it didn’t appeal to the tastes of either Tang and Song dynasty leaders? Assuming the significance that Papalexandrou attributes to artists and original audiences, there is potential for past understandings and histories to be lurking in the back of Kublai Khan’s and his subjects’ minds, resulting in a general affection for blue-and-white. The colors, blue and white, had specific mythological significance to the Mongols: some time after his Genghis Khan’s death, The Secret History of the Yuan Dynasty (元朝秘史) was written, and in it, the ancestors of Genghis Khan were detailed, beginning at Borte Chino (Blue Wolf) and his wife, Gua Maral (White Doe). This sort of belief was popular among many of the steppe peoples and can be seen as in direct relationship with the Turkic origin myth in which it was believed that all Turkic people were descendants of the 10 original sons that were raised by a mother wolf; a similar belief was seen among the Uyghurs.[7] It is here, in its color and in its existence itself, where the role of Mongol beliefs and the vague connections to other steppe beliefs most fundamentally are reflected in the brush rest.

ISLAMIC INFLUENCE

Due to the influx of mercantile interest, encouraged by the Yuan Dynasty leadership, a large number of Arab merchants began arriving in China and amassing large amounts of wealth. On numerous pen holders from the time that look nearly identical to the one this paper is referring to,[8] Persian script was often featured on the items in a cartouche— in this instance, the words khāmah (قلم) ‘pen’ is written on one side (Figure 2), and the other, dān (حامل) ‘holder’ (Figure 4) , each in a diamond cartouche. The Persian calligraphy as decorative element is reminiscent of the use of calligraphy as ornament also seen in the work of Persian architecture and ceramics, an example pictured in Figure 7: this use of calligraphy as decor could be understood to have occurred initially in largely Muslim countries due the religion’s belief in aniconism,[9] revealing another example of the hints of Muslim visual culture in this apparently Chinese item. Furthermore, a unique style of Ancient Persian script has been identified on the brush rest by academics, which has made the linguistic origins and influences of this item up for debate,[10] potentially reflecting the continuous shifting and mutual exchange that occurred between the Persian and Chinese communities, affecting even calligraphic styles of the given languages.

In Islamic tiling, blue was a popular color, especially in the areas surrounding Persia, due to the location’s proximity to abundant sources of the material; this resource would then be transported to China, providing the means for these merchants to amass great wealth and the means for feature the deep shade of blue that is well known in Chinese blue-and-white ceramics. However, as a result of the technological and economical differences of the western cultures, its use was fairly different from the use in Chinese blue-and-white porcelain. As an example, this can be seen in the Shah Mosque (Figure 8), a mosque located in Isfahan, Iran. This blue, however, was often featured in works in an opposite fashion to how it is observed in most Chinese porcelain items.

Working with negative space was a popular technique in west Asian work: the space around the subject of the work is filled with color, rather than the subject itself being created using a paint or glaze. While this can also be seen in Chinese works, it is different in scale and execution, with the Chinese version working with a thin blue glaze, an example being shown in Figure 9, and the blue in west Asian artifacts being more concrete and stark, as seen in a detail of the Shah Mosque (Figure 7), mentioned earlier, which shows the hints as to what would make blue-and-white ceramics so unique in the eyes of western audiences.

However, silhouette work, similar to the ones of the mushrooms on the paint brush holder,[11] had also been already present and popular in western parts of Asia; rather than blue and white, however, it was featured in blue and black, revealing the significance of color in the audiences’ relationship to the object. While similar in style and appearance, there was still a demand for Chinese blue-and-white in the west, considering the numerous samples of Chinese blue-and-white found in the west. However, as mentioned earlier, the shade of white porcelain created depended on the manner in which it was created, which varied from location to location. While artists in the western part of Asia created porcelain using stonepaste (also known as fritware), invented and recorded in a 1301 AD treatise by Abu’I-Qasim, from a prominent Kashan family of potters, China was using a mixture of porcelain stone, or petuntse (白墩子), and kaolin.[12], [13] Ceramics made from porcelain stone are generally much whiter in shade and much stronger than fritware.

It is this difference that could potentially be reminiscent of the work of Alfred Gell regarding the technology of enchantment: the resulting change in a few shades of white, when comparing fritware to porcelain stone, could resemble what Gell would deem “magic,” revealing what would inspire those market forces that suggested that importing the deep blue of Persian cobalt into China and that exporting ceramics with the porcelain stone base made in China was worth the effort.

MING CONTROL

With the defeat of the Mongols, came the Ming dynasty, which initially began to drift away from the blue-and-white trend established by the Yuan dynasty. However, with the rise of the fifth Ming Emperor, Zhu Zhanji, also known as the Xuande Emperor, a particular fondness for blue-and-white was reestablished.

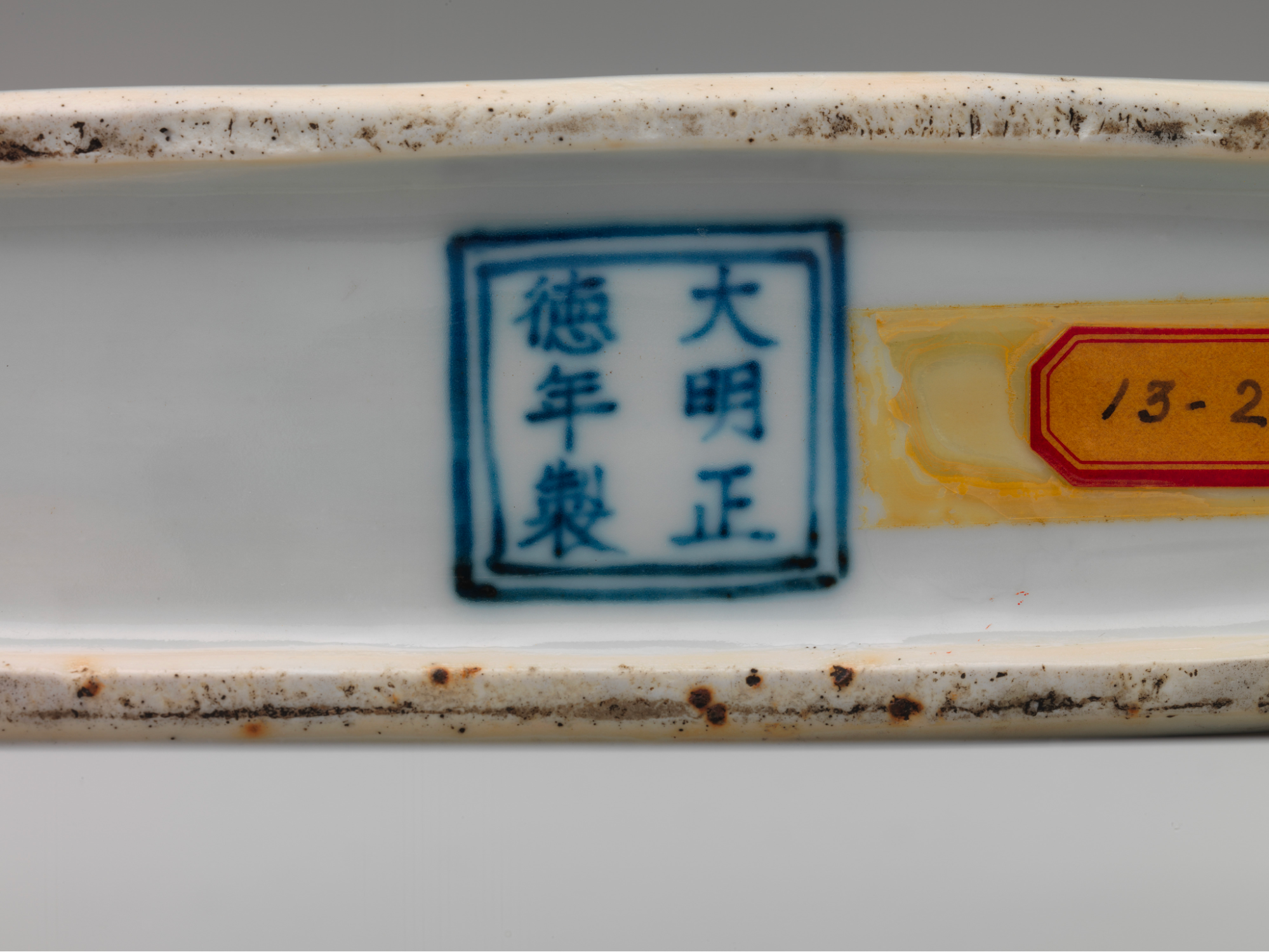

At the same time, beginning from the late 14th century, “reign marks” began to be featured on the base of ceramics made at the time, which labeled the dynasty and emperor at the time of creation at the bottom of ceramic items. Beginning with Zhengzong during the Ming dynasty, reign marks began to appear on most artesian objects created at the time, identifying themselves specifically with the given emperor.[14] The object which is the focus of this paper bears the markings of the Zhengde Emperor from the Ming dynasty on the bottom, as seen on Figure 6, reading 大明正德年制, which most directly translates to, “Made in the year of Zhengde of Ming Dynasty”. The presence of the Persian calligraphy described earlier as well as the presence of the Chinese characters coexisting on the brush rest, in the context of Papalexandrou, reveals the acknowledgement of the relationship between the coexisting Chinese and Persian presence in the area.

This acknowledgement is further strengthened in its potency when a connection to the Chinese imperial court is established: it has also been noted that the clearer and more defined the characters are on the bottom of the porcelain piece, the closer to the Emperor and his court the piece generally was.[15], [16] The clarity and precision with which the reign marks on the brush rest that this paper is focusing on (Figure 6) were painted, still clear and crisp to this day, unlike other items whose marks were blurry and sloppily applied, reveals the strong relationship between the imperial courts and this item; this relationship, formally inspired by many Persian, Islamic, and Mongol beliefs, shows a direct acknowledgement of non-Han influences by the supposedly more “traditional” (i.e. Han) Ming dynasty, emphasizing the exchange that was and had occurred at the time. However, there was still a clear traditional Han Chinese basis in many formal aspects of the brush rest, other than the presence of those reign marks.

While the arabesque on the brush holder has properties that are similar to that of west Asian arabesques, the images on it have also been identified as lingzhi scrolls, which hold Buddhist and Daoist significance. The first instance of lingzhi (灵芝) scrolls being recorded as having Daoist significance is in The Secret of Divine Immortals (神仙秘事), as it ascribes longevity to the mushrooms.[17] This iconographic significance of the mushrooms shows the direct connection established between the item and Daoist principles, which has been largely assumed to be associated with Han Chinese beliefs, showing something resembling a continuation of former Han beliefs..

The shape and form in which this brush rest takes has generally been assumed to refer to the Five Sacred Mountains, but may also have circumstantial connection to Islam— the common religion among Persians at the time— as well. The traditional Confuscian belief held that there were Five Sacred Mountains in China, each representing one of the five elements.[18] This has been interpreted as primarily of Daoist significance, which ascribed different elements to each of the five mountains. However, regarding the high number of ethnically west Asian peoples present in the area, the five mountain peaks may also hint at a relationship to Islamic beliefs, which had grown popular in the area surrounding Persia, and may have been affecting China as a result of their presence; a major crux of Islamic belief is the Five Pillars of Islam.[19] These beliefs largely structure the faith and according to some art theory, such as that of Papalexandrou, may have appealed to the mental framework of a Muslim audience.

Furthermore, there is evidence of a ruyi (如意) on the bottom of the brush holder. The ruyi is significant to Chinese tradition due to its prevalence throughout Chinese history; while it initially referred to the scepters wielded by emperors, generals, and other decision-makers from a variety of different cultures including those in India (making the origins of the ruyi itself ambiguous) for whatever intentions they wished for it to be be used for, eventually becoming a general symbol of court authority, it now specifically refers to the symbol often seen on top of these scepters, including the first one discovered in 1986, a ninth century scepter with the shape on top of it.[20] The use of such an image on the brush rest as decor, an ethnically vague symbol of authority, once again emphasizes the proximity of this item to power as well as the clear acknowledgement of the cultural intersections that resulted in this item’s creation.

ITEM-SPECIFIC CONTEXT

Blue-and-white porcelain was perceived as luxurious, and was therefore often used for diplomatic gifts after the rise of their popularity. Objects made for export were often large serving plates, teapots, vases, covered jars and other household items not normally used in China, and meant to specifically appeal to audiences through their use function.[21] Objects meant for office use, such as this brush rest, would not have been typically made for export: however, the clear appeal to western Asian cultural groups as seen in this item implies that the western Asian population there was less temporal than typically assumed. Zhengde desk porcelains with Arabic and Persian markings have not been uncovered in the Topkapi Palace or the Ardebil shrine, where other porcelain items such as serving dishes and bowls with a Zhengde label and similar Persian and Arabic markings were found,[22] implying that these office objects were generally never treated like consumer goods, meant to be made, purchased, transported, and then resold again.

The Zhengde emperor himself was notably interested in west Asian cultures from the very beginning of his reign: he dressed in the fashion of the cultures and had even instantiated a law forbidding the consumption of pork, sparking rumors of his conversion to Islam. The population of practicing Muslims had been exceptionally high in China at the time, in and around the area surrounding the capital, largely due to this great industrial process and its associated mercantile markets, with the resulting cultural exchanges permeating through the beliefs, behaviors, and aesthetic choices of the people in the time and place.[23] And yet, the Ming dynasty is still perceived nowadays as a return to the culture and style of the traditional Han Chinese beliefs and practices, when the items from the time are clearly, tangibly anything but that, with this brush rest functioning as an example. It was an item made for a group of people living in a specific time and place whose existence and presence depended on a process of cultural exchange occurring that facilitated the item’s creation.

CONCLUSION

Bonnie Cheng claims that, when speaking of narratives of cultural exchange, it’s important to note that the process is never one-sided and never complete, regardless of how those changes manifest themselves. While the work of Papalexandrou could be interpreted as a world of binaries due to his use of the word, “hybrid,” as it implies the presence of a unhybrid and potentially “pure” culture, his understanding of frameworks is significant: almost Freudian, Papalexandrou has detailed the significance of exposure in shaping the frameworks of both, of groups and of individuals. It is exposure that shapes understanding, and while the Yuan Dynasty may have fallen, the following one could not do anything to return those frameworks back to their original state before having been exposed to a 13th century version of what would be defined as “multiculturalism” today.

The Ming dynasty, in most contemporary, generalized understandings of Chinese history, functions as primarily a foil to the Yuan dynasty. While this may appear reasonable on a superficial level, there are unacknowledged intricacies that result as a consequence and will always last, permeating throughout contemporary Chinese history. This would eventually result in “China” being another term for the porcelain that first became famous for being created in the geographic that is now referred to as China, without necessarily fitting all too many definitions and understandings as to what it means for something to be Chinese, leaving English-speakers with a potentially uniquely inhibited understanding of the medium, forever affecting their own frameworks.

Appendix of Images

Figure 1: Brush Rest with Persian Inscription (front), early 16th century

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/42528

Figure 2: Brush Rest with Persian Inscription (front calligraphy), early 16th century

Figure 2: Brush Rest with Persian Inscription (front calligraphy), early 16th century

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/42528

Figure 3: Brush Rest with Persian Inscription (back), early 16th century

Figure 3: Brush Rest with Persian Inscription (back), early 16th century

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/42528

Figure 4: Brush Rest with Persian Inscription (back calligraphy), early 16th century

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/42528

Figure 5: Brush Rest with Persian Inscription (bottom), early 16th century

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/42528

Figure 6: Brush Rest with Persian Inscription (bottom calligraphy), early 16th century

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/42528

Figure 7: Shah Mosque, Inscription on the wall of the Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque, Isfahan, Iran, 1611-1629

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sheikh_Lotf_Allah_mosque_-_harem_wall_detail.jpg

Figure 8: Shah Mosque, a 3D panorama of interior of the main prayer hall, Isfahan, Iran, 1611-1629

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Imam_Mosque_3Daa.jpg

Figure 9: Bowl with Dragons, Peony Scrolls, and Band of Lingzhi Mushrooms, 1522–1566

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/21282/bowl-with-dragons-peony-scrolls-and-band-of-lingzhi-mushrooms

Bibliography

Aigle, Denise. “The Transformation of a Myth of Origins, Genghis Khan and Timur.” Essay. In The Mongol Empire between Myth and Reality: Studies in Anthropological History, 124–27. Leiden, NL: Brill, 2014.

Atasoy, Nurhan, Yanni Petsopoulos, and Julian Raby. “V. The Making of an Iznik Pot.” Essay. In Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey, 50–51. London: Alexandria Press in association with Laurence King, 1994.

Bagliani, Paravicini Agostino, Chiara Crisciani, and Dominic Steavu. “The Marvelous Fungus and The Secret of Divine Immortals.” Essay. In Longevity and Immortality: Europe, Islam, Asia, 353–80. Firenze, CA: Sismel, Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2018.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Pillars of Islam.” Encyclopædia Britannica, March 13, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pillars-of-Islam.

Carswell, John. Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain around the World. London: British Museum Press, 2000.

Davison, Gerald. The Handbook of Marks on Chinese Ceramics. London: Han-Shan Tang Books, 1994.

Dillon, Michael. “Transport and Marketing in the Development of the Jingdezhen Porcelain Industry during the Ming and Qing Dynasties.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 35, no. 3 (1992): 278–90. https://doi.org/10.1163/156852092x00156.

Garner, Harry. Oriental Blue and White. 3rd ed. London: Faber, 1954.

Gerritsen, Anne. “Fragments of a Global Past: Ceramics Manufacture in Song-Yuan-Ming Jingdezhen.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 52, no. 1 (2009): 117–52. https://doi.org/10.1163/156852009x405366.

Gerritsen, Anne. “Porcelain and the Material Culture of the Mongol-Yuan Court.” Journal of Early Modern History 16, no. 3 (2012): 241–73. https://doi.org/10.1163/157006512x644793.

Jia, Jinhua. “Formation of the Traditional Chinese State Ritual System of Sacrifice to Mountain and Water Spirits.” Religions 12, no. 5 (2021): 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050319.

Kieschnick, John. “Chapter 2: Symbolism.” Essay. In The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture, 83–156. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Li, Weidong, Xiaoke Lu, Hongjie Luo, Xinmin Sun, Lanhua Liu, Zhiwen Zhao, and Musen Guo. “A Landmark in the History of Chinese Ceramics: The Invention of Blue-and-White Porcelain in the Tang Dynasty (618–907 A.D.).” STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research 3, no. 2 (2016): 358–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/20548923.2016.1272310.

McCausland, Shane. “Blue-and-White, The Yuan Global Brand.” Essay. In The Mongol Century: Visual Cultures of Yuan China, 1271-1368. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press, 2014.

Pierson, Stacey. “Beyond Vessels: Chinese Ceramics in the Modern World.” Essay. In Chinese Ceramics: A Design History, 122–23. London: V & A, 2009.

Prazniak, Roxann. “Dadu in Khitai (Great Yuan).” Essay. In Sudden Appearances: The Mongol Turn in Commerce, Belief, and Art. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2021.

Valenstein, Suzanne G., and Metropolitan Museum of Art. A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.

[1] Weidong Li et al., “A Landmark in the History of Chinese Ceramics: The Invention of Blue-and-White Porcelain in the Tang Dynasty (618–907 A.D.),” STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research 3, no. 2 (2016): pp. 358-365, https://doi.org/10.1080/20548923.2016.1272310.

[2] Anne Gerritsen, “Fragments of a Global Past: Ceramics Manufacture in Song-Yuan-Ming Jingdezhen,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 52, no. 1 (2009): pp. 117-152, https://doi.org/10.1163/156852009x405366, 135-136.

[3] Ibid, 137.

[4] Shane McCausland, “Blue-and-White, The Yuan Global Brand,” in The Mongol Century: Visual Cultures of Yuan China, 1271-1368 (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press, 2014), 227.

[5] Roxann Prazniak, “Dadu in Khitai (Great Yuan),” in Sudden Appearances: The Mongol Turn in Commerce, Belief, and Art (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2021).

[6] Anne Gerritsen, “Porcelain and the Material Culture of the Mongol-Yuan Court,” Journal of Early Modern History 16, no. 3 (2012): pp. 241-273, https://doi.org/10.1163/157006512x644793.

[7] Denise Aigle, “The Transformation of a Myth of Origins, Genghis Khan and Timur,” in The Mongol Empire between Myth and Reality: Studies in Anthropological History (Leiden, NL: Brill, 2014), pp. 124-127.

[8] Which, in addition, truly highlights the degree to which the process of porcelain production was methodical and industrialized at this point in time; nearly indistinguishable from each other, only the hints of age (cracks, repairs, fading colors) truly differentiate the brush rests from one another.

[9] Mahdi, Muhsin, Schimmel, Annemarie and Rahman, Fazlur. "Islam," Encyclopedia Britannica, August 17, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Islam.

[10] McCausland, 227.

[11] The iconographical significance of which will be detailed later in this paper.

[12] Nurhan Atasoy, Yanni Petsopoulos, and Julian Raby, “V. The Making of an Iznik Pot,” in Iznik: The Pottery of Ottoman Turkey (London: Alexandria Press in association with Laurence King, 1994), pp. 50-51.

[13] Suzanne G. Valenstein and Metropolitan Museum of Art, A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics (New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975), 72.

[14] Stacey Pierson, “Beyond Vessels: Chinese Ceramics in the Modern World,” in Chinese Ceramics: A Design History (London: V & A, 2009), pp. 122-123.

[15] Ibid, pp. 122-123.

[16] Gerald Davison, The Handbook of Marks on Chinese Ceramics (London: Han-Shan Tang Books, 1994), 12-13.

[17] Paravicini Agostino Bagliani, Chiara Crisciani, and Dominic Steavu, “The Marvelous Fungus and The Secret of Divine Immortals,” in Longevity and Immortality: Europe, Islam, Asia (Firenze, CA: Sismel, Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2018), pp. 353-380.

[18] Jinhua Jia, “Formation of the Traditional Chinese State Ritual System of Sacrifice to Mountain and Water Spirits,” Religions 12, no. 5 (2021): p. 319, https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050319.

[19] T. Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Pillars of Islam,” Encyclopædia Britannica, March 13, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pillars-of-Islam.

[20] John Kieschnick, “Chapter 2: Symbolism,” in The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003), pp. 143-147.

[21] McCausland, 227.

[22] John Carswell, Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain around the World (London: British Museum Press, 2000), 138.

[23] Harry Garner, Oriental Blue and White, 3rd ed. (London: Faber, 1954), 29-32.