Introduction

Sciences are based in the tangible and observable world. Memory, unfortunately, is neither of those. It is ephemeral, and in an attempt to make it permanent, many civilizations throughout history have chosen to use objects to create an illusion of a perennial memory, affecting future generations. Such objects are often made monumental in scale or attempt to be monumental in effect: and with the exception of site-specific monuments in remote locations, monuments are often placed in high-traffic urban spaces that maximize their viewership and their effect. Especially for monuments that are colossal in scale, these objects begin to fundamentally shape the environment of the people who live in sight of them, changing the skyline with their construction. Even details of the surrounding location become significant and fought over. This paper will be a case study of Washington Square Park and its monuments, considering its historical relevance, setting for the Washington Square Arch, and its still-popular role as a meeting place for the youth of New York City.

There are less than 20 still-standing triumphal arches in the United States, one of which stands in Washington Square Park, influencing the horizon of downtown Manhattan. However, even the creation of the park itself, having occurred more than half a century before, was controversial and politically motivated, being in itself a monumental act that would change the skyline and living memory from the moment the decision was made. However, those who choose to make the decision and what was chosen to be remembered was selective, and continuously, from its very beginning, Washington Square Park has been a mirror of its surrounding inhabitants; revealing patterns of bureaucracy and class conflict in different dimensions, it has mimicked American capitalist democracy in its strengths and weaknesses over time, clearly visible even today.

Origins

First settled in the late 17th century, the region north of what was (at the time) recently renamed New York was being settled by the wealthy: it was nicknamed Greenwich Village, the residents having been reminded of Greenwich, England, which was the perfect location for a country estate. To the dismay of this affluent population, during the yellow fever epidemics of the early 19th century, a plot of land in the greenspace was designated as a government cemetery for victims of yellow fever, despite protests from the wealthy, quickly attracting tramps and prostitutes.[1] It functioned as a graveyard until May 24, 1824, when a New York Evening Post article was released under the headline, “Resurrectionist,” telling the story of an escaped prisoner who had taken refuge in one of the graves and then had been discovered by a groundskeeper during the night. Burials in the area then ceased in almost exactly a year.[2] This, from the beginning, shows the appeal to wealth in the city and in the location.

This sort of appeal, especially at the time of the park’s establishment, permeated into government authority as well. Sailor’s Snug Harbor, once called The Marine Society (of whom George Washington was a part), was a charitable trust meant to help indigent seamen. Down on their luck and receiving no public tax support, the trust needed more rents on their property that lay east of Fifth Avenue. They owned 21 acres of farmland, most of which touched the northern boundary of the potter’s field. Philip Hone, mayor of New York and a trustee of Sailor’s Snug Harbor, wanted to help; having seen the success of establishing Hudson Square in the 1820s, which boosted the economic success of Trinity Church, he decided to implement a similar plan for the trust. However, establishing the park would require changing the Commissioner’s Plan, which at that point in time was controlled by state legislature to avoid this kind of special interest activities. Furthermore, land in Manhattan was also growing more and more valuable, the old potter’s field being worth 23 times more in 1826 than what the city had paid for it in 1767,[3] making demand for the plot of land, whether for real estate development or otherwise, that much more competitive. For the area to be declared a park, careful and intentional planning had to be involved.

Almost two decades earlier, a 270-acre parade ground had been created in preparation for The War of 1812 right above 23rd Street and was cut down in size after the war ended in 1814. When the Common Council met in February 1826, they began to question the Parade Grounds’ substantial size and reason for being. Hone ensured that he’d be present at the time of discussion, and had mustered support for the movement of the parade grounds to the former potter’s field, meant to provide a location for the local military’s ceremonial public displays of unity and glory, especially at a time when the military was made up of local citizens.[4] While true, the local citizenry at the time was increasingly becoming wealthy, masking the subtle appeal to the upper crust population in the area.

This patriotic approach was further strengthened through the choice in name for the new park. The square’s surrounding north-south streets were already named after heroic generals of the Revolution, so in order to especially highlight the role of George Washington, the new square was named the “Washington Military Parade Ground”. The name also significantly enhanced lot values,[5] as an additional benefit. Once the parade grounds were declared, the new potter’s field was designated to the location that would eventually contain Bryant Park and the New York Public Library,[6] revealing the repeated exploitation of circumstance in the city as the dead are disregarded only then when it is convenient for the people in power.

Washington Square would be in need of expansion to compete with Belgrave Square, which Hone sought to emulate. After 10 months of negotiations, eight owners with 12 contiguous lots built uniform terrace housing, similar to those lining Regent Park. While this didn’t necessarily appeal to the egalitarian tendencies of America at the time, due to the intention to make each row house look as palatial as possible, it enclosed the square in an aesthetically pleasing fashion.[7] Prioritizing the property value, competitiveness with other popular squares, and physical appearance of the surrounding buildings, even engaging in indulgent, ritzy design when at the same time, in October 1827, the court had just approved the council’s decision to expand the square, and denoted the park as a “Public Place,” unlike London’s squares, which were explicitly private,[8] providing a superficial title of democracy and universal rights, while still engaging with the same practices meant to exclude lower-class groups, increasing the cost of living near the park.

When these rowhouses first went up for sale, they were advertised in the New York Gazette of January 6, 1827, under the heading, “To Capitalists”.[9] And his plan to increase the property worked: “capitalist”, aristocratic families with lineage to the Mayflower began to move to the area, including but not limited to the Taylors, Griswolds, and Johnstons.[10]

Of note is one of the greatest protests against the expansion: the dead of the Scotch Presbyterian Church would be disrupted by it.[11] Regardless of the predominantly British and Scottish wealthy population in the area, the demand for more space for the park to compete with those seen in Britain forced the park to increase in size. The protests were ignored in the name of higher property values and to provide a luxurious location for the rich. This was so desired that even the stables were located a bit more south, in the working-class area of Greenwich, to ensure that the smell and filth did not contaminate the beauty directly surrounding the park.[12]

The University of the City of New York, later named New York University (NYU), paid a steep price for a new building, starting with $40,000 for an entire blockfront in 1832, which left the university with $66.46 of their original funds. The university sank into debt, not paying professors and mortgaging their books. Incorporating Gothic chapels, some towers and buttresses protruded over the building line, which required the shortening of the marble for the first three floors in 1834. This resulted in the use of convict labor from Sing-Sing prison, rather than from local stonecutters.

The local stonecutters then rebelled, smashing windows in the surrounding areas as well as marble mantles in protest of New York University’s decision,[13] highlighting the weakness of the high-class indulgence demanded by the institution, which ultimately resulted in little change for the local stonecutters. They converged on construction sides with rocks and brickbats, and to protect the building, New York’s National Guard was called in and stayed in Washington Square for four days and nights until peace returned to the area. The ability for the park to become a mock-battleground for class conflict most clearly begins here. Afterward, NYU’s financial strife resulted in a need to rent out its space to artists and other creative personalities, becoming a haven for one of the city’s earliest bohemian communities,[14] functioning as a major accelerating force for the first introduction of a bohemian, less affluent community into the area directly surrounding the park.

However, the conflicts that occured at the time were not purely economically driven. In 1849, after five years of accusations and sabotaged performances between the British star William C. Macready and Edwin Forrest, a bombastic player who was beloved by the working-class Irish, reached a boiling point, manifesting as the consequence of ethnic tensions. On the second night of Macready’s performance at Astor Place, hooligans started throwing cobblestones at the opera house. Units of the Seventh Regiment were called in and 21 rioters and bystanders were killed,[15] showing the lengths that the authorities would implement to maintain an outward peace in the area, especially for those of a higher socioeconomic class.

Theaters and opera houses became a popular attraction for local genteel population, spreading the beliefs of bohemianism; however, not all were accommodating to the artists that were needed to supply the arts being consumed, the New York Times once claiming: that “the Bohemian cannot be called a useful member of society, and it is not an encouraging sign for us that the tribe has become so numerous among as to form a distinct and recognizable class who do not object to being called by that name”.[16]

However, once the Civil War began in 1861, this began to change, as the wealthy began to move uptown, and poorer, working-class families began to move into the village,[17] the wealthy typically moving out and leasing their old homes to these lower-status individuals,[18] especially Italians and artists that loved the cheap but delicious food that came with Italian cafe life.[19]

Antebellum New York City

In 1863, draft riots occurred when predominantly Irish laborers couldn’t afford a substitute or the $300 exception fee after the first draft for the Civil War. The emancipation of blacks also made whites afraid for their job security in the city. These workingmen wandered around the park, beating black men and cutting telephone wires. 105 people had been killed as a result of the riots, making these riots the most violent public disturbance in American history.[20] This had further accelerated the process of the wealthy beginning to flee the area into uptown Manhattan. These ethnic tensions remained after the riot, dividing the groups by religious biases as well as infighting led to events such as the Orange Riots erupting in 1870-1871 between Irish Catholic and Scottish Protestant immigrants, resulting in at least 62 deaths.[21]

In the 1870s, the majority Irish Catholic Tammany Hall, led by William “Boss” Tweed (who would soon fall from power due to his inability to control the Irish population during the Orange Riots), encouraged the renovation of many of the city’s parks, leading to Washington Square’s new gaslight lamp posts and curved, leisurely walkways being designed by Frederick Law Olmsted,[22] meant to make the former military ground feel more like a park. The original fountain, built in 1852, was also replaced with a smaller, 72’ diameter fountain in order to make room for the main roadway,[23] which would in the coming century become remarkably significant as capitalist priorities and goals intensified, but at the time appealed to the increasing need for the trasport of commercial goods and people with the antebellum economy. Olmsted’s redesign of the park would create three new streets connecting to the square, worrying the wealthy that easier access to the square would encourage criminals to attack the park’s visitors,[24] revealing a continuation of the concerns over class conflict by the wealthy, similar to those concerns from when the park was merely a potter’s field. In 1878, the square was officially legislated as an official public park.[25]

The Creation of the Arch

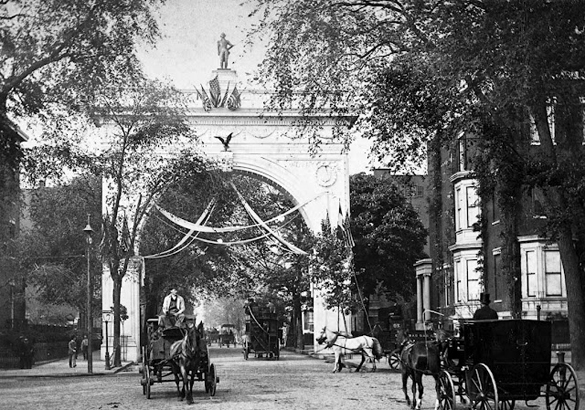

A bit more than a decade later, in order to celebrate the centennial of George Washington’s inauguration as president, a triumphal arch was built in the center of the park out of plaster and wood (fig.1). Meant to be a temporary installation, the arch was eventually torn down: however, the arch had been praised so much by the elite, a permanent version made out of marble was commissioned, featuring two statues of Washington as commander in chief and as president.[26] However, it seemed like only one of Washington's roles was meant to be emphasized, considering the select words that were chosen at the dedication of the arch.

The orator who spoke at the dedication of the marble Washington Square Arch in 1895 was Horace Porter, whose speech, focusing on the successes of Washington, emphasized the military victory against Britain during the American Revolution, rather than the invention of American democracy, marking a change in the form of Revolutionary memory after the Civil War, which was once hailed as the victory of democracy over tyranny. This change and choice in emphasis made sense, considering the subtle theme in the speech surrounding the mending of the gap between the increasingly stratified poor and wealthy that was becoming more dramatic during the Gilded Age, and coming together behind the military victories of Washington, rather than focusing on the political.[27] It was easier to unite behind blind patriotism than concrete politics, as the conventionally wealthy that once lived around the park began to flee the area due to the increased commercialization and waves of immigrantion in the area, physically increasing the distance between the poor and rich.

After the Civil War, the economy had boomed, resulting in the bettering of lives of all New Yorkers. The city’s industrial production and its property values more than doubled in the time between 1860 and 1870,[28] directly leading to the Gilded Age. William Rhinelander Stewart, a neighborhood resident and part of one of New York’s Knickerbocker families, a group of prominent and aristocratic Dutch and English family names, led the fundraising effort for the building of the arch,[29] revealing the personal initiative taken up by either those who left most guilty at their success, influenced by Bohemian thought in the area, or those who genuinely wanted to hide the deep inequality of the time. Regardless, $128,000 was spent on the creation of the arch, of which about four-fifths was funded by 400 individual, personal donors.[30]

Furthermore, at its height and position, the arch invoked the grandeur of London and Paris,[31] once again attempting to increase the value of the surrounding land (and thus the rents and price of living) in the area, but also highlighting an overall changing time in the city. In 1872, the Domestic Sewing Machine Company built one of New York City’s first skyscrapers, marking a change in the skyline, in the economy, and in the city,[32] and the creation of this arch may have also functioned as an attempt for the park to assert its presence in the city as skyscrapers began to pop up all over the city.

The Statue of Guisseppe Garibaldi

Another patriotic figure also became commemorated in the park as a larger-than-life-size monument (fig. 3) in 1888: Giuseppe Garibaldi, a military celebrity of the mid-to-late 19th century; he was a leader of Italy’s 1814-71 struggle for independence. At the time, many Americans actively supported Garibaldi and the Risorgimento, seeing in the figure a symbol of how anarchy can transform into authority, standing for patriotism over politics,[33] which could also be seen as a call to unity after the political divide present in the United States after the Civil War. This is further supported by the funding of the statue by Italian immigrants of all classes, who had recently immigrated to the United States in masses, largely disconnected from the Civil War, unlike the Irish working classes.[34]

Like heroic images of Washington, the image of Garibaldi was that of a romantic, humbled hero, seen in his plain clothes and large scale of the monument, further elevated on a pedestal. In the papers, he was advertised as “Garibaldi, the Washington of Italy,” and the phrase was repeated frequently enough to become a catchphrase.[35] By positioning this military hero in the context of the arch, Washington’s role as a military hero is once again emphasised, as he was by Porter’s speech, whether intentionally or unintentionally.

The Statue of Alexander Lyman Holley

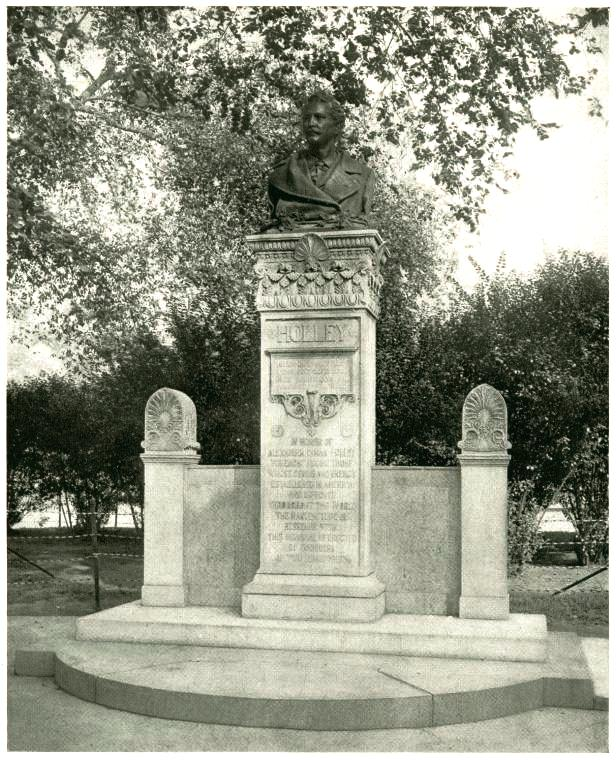

Upon his death in Brooklyn at age 49 in 1882, Alexander Lyman Holley was in the process of creating professional societies, three of which jointly raised funds to commission his memorial in the park: the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), the Institute of Mining, Metallurgical and Petroleum Engineers (AIME), and the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE). These groups, important to the Gilded Age and Industrial Revolution, reflected the priorities of industrialists and their cross-ethnic nature reflected their differences from both, the working class and upper crust populations: less dramatic than the arch and the Garibaldi statue, this one was clearly different. The memorial, a bronze bust mounted on a tripartite pedestal made of limestone, was dedicated on October 2, 1890, and was witnessed by a group of engineers from different societies, including some from Germany and France.[36]

However, some considered the choice in location for the bust to be poor. Specifically within the park, the location was perceived to be easily ignored. But in spite of that, it is possible that the bust’s small scale, especially positioned near the massive arch, would always make it blend into the background, which was to be seen as the bust was later moved within the park even more off to the side. This was also somewhat addressed in the criticisms of the choice of the park itself, lacking direct relevance to the identity of Holley. The New York Times suggested that the statue be moved to the grounds of Columbia University or the town of Troy, due to Holley’s history with the places.[37]

But this issue of becoming outdated and irrelevant began to affect the arch and the old row houses as well, as the surrounding area became increasingly commercialized. In the 1890s, new commercial buildings began to dwarf the older ones seen in the area. Henry James, the author of Washington Square, born two doors down from the old NYU building, claimed that his birthplace had been “ruthlessly suppressed” when it was torn down,[38] revealing the suppression that older residents viewed of the capitalist changes, marking a standstill for the potential development of the park, but the marked continuation for the capitalist endeavors surrounding it.

Artists & The Non-Bourgeois

At the turn of the 20th century, it seemed like there were beginning to be more artists than immigrants in the area, and upper-middle-class families and professionals moved into the residences surrounding the park, as new subway lines were being built nearby and Greenwich Village became the location for shops and restaurants. The area became increasingly visited by intellectuals and alternative types: rebellious artists, painters, writers, and social commentators, exasperating a pattern already seen since the mid-19th century. This continued up until the Great Depression when the attention of federal investigators was drawn in the 1930s due to the prominence of anti-war and pro-worker support in local independent news journals. The artistic outlook of these artists and musicians that spent a majority of their time in the park took it over more as the street benches got vandalized, and the lawns were allowed to turn brown, and the fountain began to leak: and yet, its residents found it comfortable.[39]

Between 1870 and 1970, a road ran through the park (fig. 5), and starting in the 1930s, the park commissioner in New York City at the time, Robert Moses, had decided that the park needed to be renovated, and that a larger, more efficient road needed to cut through it in order to alleviate the surrounding traffic, showing the extremes that this commercialization was reaching: efficiency is a priority for hyper-capitalist societies, and for this efficiency to permeate in Greenwich Village, a road through the park was needed. In response, Jane Jacobs, Shirley Hayes, along with neighborhood committees fought to remove all traffic from the park, including the elimination of the already-existing roadway that connected 5th Avenue and Washington Square South, going through the arch,[40] revealing the level of control that these locals did have even though the population was no longer of the true, aristocratic elite that now resided uptown.

In 1958, Lewis Mumford, the architectural critic at the New Yorker, wrote in a press release that Moses’ actual intentions were to extend the name “Fifth Avenue” to a region of lower Manhattan by literally extending the avenue through the park. This would increase the value of the surrounding real estate, encouraging real estate developers and the private sector (as well a not-for-profit institution, NYU) to revitalize the increasingly tawdry park,[41] which surprisingly mirrors the desires of Philip Hone in the 19th century to create the park in the first place. In this case, however, the man did not succeed, revealing a weakening government, especially in relation to independent actors.

The Flag Staff

A commemorative flagpole had been built in 1920 to honor those who had died during World War I. The names of the men from the surrounding areas were written all along the base of the flagpole, with the exception of most African American and Italian-American men who had also equally sacrificed their lives for their country,[42] and the flagpole having been funded by the Washington Square Association, a neighborhood group revealed the exclusive patriotism its members showed.[43] Initially, the flagpole had been positioned so that it could be seen directly under the arch when looked at from 5th Avenue (fig. 6), but was moved in 1970 with the removal of the road going through the park and is now surprisingly hard to find among the trees and towering buildings, even though it is a flagpole (fig. 7). This physical shift away from center stage revealed the shift away from the patriotism that the late 19th and early 20th centuries intended to push using these public monuments.

Becoming NYU

In the meantime, NYU was buying up the properties surrounding the park. Bobst Library, announced in 1963 and completed in 1974, is a massive, fortress-like red sandstone (fig. 8) that stands at the southeast corner of the park casts a shadow over the park,[44] which would shape the skyline of the Fifteenth Ward. Initially controversial, this building would foreshadow the future effect of the institution on the area.[45] In the 1970s and early 1980s, the future of the university was in doubt, repeatedly approaching bankruptcy due to low enrollment and high crime rate; but with the economic boom of the late 20th century, NYU and their magnate-heavy board of directors would begin to engage significantly in the real-estate market of downtown Manhattan, working with the process of gentrification that was already taking over Manhattan. Like the wealthy did with the poor in the first century of its existence, Washington Square and its surrounding areas were intentionally manipulated to once again increase rents and price of living for the area.[46]

Unfortunately for the park and its interior, the park’s setting for political protests in the 1960s and 1970s resulted in the base of the arch being covered in posters and graffiti, which was then repainted over in the 1990s. The area around the arch was also cordoned off in the year 1990, due to the hazard posed by falling fragments, as a result of the crumbling rock and long-term water damage, making it that much harder to be enjoyed up close by the park’s visitors. In 1997, partial funding allowed for the partial intervention of A. Ottovino Corp. to remove more paint and graffiti along the base of the arch and the installation of a new roof for the arch,[47] but the inability to fund the full repair of the arch showed the lack of care and money that the government and the remaining locals had, especially for the focused improvement of the park.

Through the Adopt-A-Monument Program, the monument of Alexander Lyman Holley was preserved and maintained in 1990. Half of this process was funded by the ASME Council on Public Affairs and ASME Metropolitan Section, AIME, ASCE, and the Steel Service Center Institute, while the other half was equally funded by Save Outdoor Sculpture! (SOS!), a program sponsored by the Heritage Preservation and the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, and underwritten by Target Stores and the National Endowment for the Arts.[48] Like its origins, the maintenance of the sculpture was paid for by the partially impartial people of science who had an apolitical appreciation for the figure, as well as a corporation that could also benefit from some good press.

However, Garibaldi’s statue had been more aggressively vandalized, even forcing his scabbard into storage due to the extensive damage on it, perhaps due to its more audacious and political presentation.[49] The statue was cleaned in 1998, funded by the City Parks Foundation Monuments Conservation Program, and the scabbard was repaired and restored to its original location in part by The American Express Company,[50] since the long-gone immigrant community had left the area long ago, and the financial services company could have benefited from some charitable virtue signaling. Although many NYU students used the park and the campus had seemingly begun to swallow the park into itself, none of this was funded by NYU’s (upwards of) multi million dollar endowment.

Contemporary Renovations & Memorials

In 2005, there was to be another renovation of the park: George Vellonakis, the architect for the Parks Department since 1986, would be the one to design it at a cost of $16 million.[51] His changes would involve the following: the relocation of a dog park, the placement of a new park in the location of an old park’s remnants (at the time three large asphalt mounds, housing the neighborhood rats), and the replacement of a plaza with a lawn.[52] Regardless of the direct improvements, he was hoping to accomplish, there was pushback.

These renovations would largely change the manner in which people would interact with the park, rather than fixing the park’s monuments, which, as mentioned earlier, were largely in disrepair. This economic, utilitarian approach focused on the visitor and their comfort, even if the experience had become false and largely manufactured. Before then, the renovations to the park were meant to merely facilitate new uses and to create new kinds of aesthetics, but in this scenario, there was a unique regression: reintroducing gaslight lamp posts and Victorian-era benches.

Luther Harris was one vocal opponent, who claimed that the plan would ruin the current layout that belongs in the naturalistic/Olmsted tradition. According to Harris, “The insensitive Parks Department wants the retro look and feel of an Old Town Square and inappropriate classical symmetry, a bogus interpretation of history,” especially through the removal of the 70s style architecture that Harris himself had last seen. Some went as far to claim that the renovations the park into what some called a “Disney-like historic themed landscape”.[53]

However, there were also examples of performative pushback, such as those who opposed the plan in fears of gentrification and engaged with highly performative acts of protest. During one community meeting between the Department of Parks, demonstrators showed up with their mouths taped over.[54] Notwithstanding, without the influence of the Department of Parks, the area itself had already become gentrified; and if this approach, focused on gentrification, is to be taken seriously, it appears as if the gentrified park was being marked upon by the wealthy, surrounding area, rather than the other way around. The halting of the process would have merely slowed down the gentrification, rather than stopping it all together.

Conclusion

This paper has gone over about four centuries of history, following the major changes and evolutions of Washington Square Park, with a focus on its monuments. With every change, funds and requests had to be made by those in power. However, regardless of America’s insistence on the fundamentals of the American Dream and democracy itself, those in power change and evolve with time. While at first, it appeared that those in charge were those in government, it unveiled itself to eventually become the wealthy. With the rise of the Industrial Revolution, commercialization took over the reins from the personal desires of the higher class and it appeared as if the people of Greenwich Village were at the will and whim of all capitalist enterprise with its focus on efficiency and short-term practicality, eventually appearing to come to a halt with the success of Jane Jacobs against Robert Moses and his road.

However, it appears that now NYU and their board of directors is the institution that pulls the strings behind the curtain now. And while carrying a facade of a nonprofit institution of higher education, the financers behave in a more selfish manner, as if the word “nonprofit” was gilding the true motivations.[55] Be it so it may, this pattern of shifting power has occurred time and time again, reflected directly in the treatment of objects in the public space of Washington Square Park, and was not the first time that similar labels were used to excuse such exploitative behavior: especially regarding the direct motivation of Philip Hone in establishing the park in the first place.

Many memorials have been placed in the park over the years— a recent example being one for black victims of police brutality (fig. 9)— but not all were stopped from their ephemeral state the way the plaster arch was. Many of these ephemeral memorials end up merely cleaned up by sanitation with the only deciding factor being how much time the memorial is given before the people or authorities deem it so (fig. 10), and only those that are literally purchased from the Department of Parks as living memorials (fig. 11) are allowed to last. American democratic capitalism and its processes at its finest.

Works Cited

Figure 1: White, Stanford. Original Washington Square Arch. 1889, The Dunne Archives, LLC

Figure 2: White, Stanford. Marble Washington Square Arch. 1900, Detroit Publishing Co.

Figure 3: Turini, Giuseppe. Statue of Giuseppe Garibaldi. 1888.

Figure 4: Ward, John Quincy Adams. Bust of Alexander Lyman Holley. 1889.

Figure 5: “Cars, Washington Square Park, Aerial View,” circa 1960-69, Washington Square Park and Washington Square Area Image Collection, NYU Bobst Library Archives.

Figure 6: Flagpole Under Arch as seen from Fifth Avenue, 1920. Art Commission of the City of New York.

Figure 7: McKim, Mead, and White. World War I Memorial Flagstaff. April 20, 2021.

Figure 8: Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, April 22, 2011. https://www.flickr.com/photos/sbc9/5850770567

Figure 9: Memorial for Black Victims of Police Brutality in front of Tisch Fountain. April 20th, 2021.

Figure 10: Means, Curtis. Washington Square the morning after people celebrate the city’s return to near-normality after the COVID-19 Pandemic. May 15, 2021. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-9582281/New-Yorks-Washington-Square-Park-resembles-dirty-garbage-dump-morning-huge-party.html

Figure 11: Plaque on Park Bench Advertising Living Memorials. April 20, 2021.

Bibliography

“ALEXANDER L. HOLLEY.; Interest in Troy in the Proper Site for. His Memorial Bust.” The New York Times, 19 Aug. 1901, p. 6.

“Alexander Lyman Holley.” Park Information, Official Website of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, www.nycgovparks.org/parks/washington-square-park/monuments/735.

Berthold, Dennis. “Melville, Garibaldi, and the Medusa of Revolution.” American Literary History 9, no. 3 (1997): 425–59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/490175.

Brown, Thomas. “VISIONS of VICTORY.” Civil War Monuments and the Militarization of America, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2019, pp. 186–231. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469653761_brown.7. Accessed 21 Apr. 2021.

Finn, Robert. “The Designer Who Would Change the Village Eden.” The New York Times, 13 May 2005, p. 2. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/13/nyregion/the-designer-who-would-change-the-village-eden.html.

Flint, Anthony. Wrestling with Moses: How Jane Jacobs Took on New York's Master Builder and Transformed the American City. Random House, 2009.

Folpe, Emily Kies. It Happened on Washington Square. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

Goode, Erich. The Taming of New York's Washington Square: a Wild Civility. New York: New York University Press, 2018.

Harris, Luther H. Around Washington Square: an Illustrated History of Greenwich Village. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

Krause, Monika. The University against Itself the NYU Strike and the Future of the Academic Workplace. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2008.

Rabinowitz, Mark, and Robin Gerstad. “‘Let Us Raise a Standard...": The Preservation of Washington Square Arch in New York City.” APT Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology, vol. 36, no. 2/3, 2005, pp. 47–55. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40004704. Accessed 21 Apr. 2021.

Ulam, Alex. “SQUARE DEAL ?” Landscape Architecture, vol. 96, no. 3, 2006, pp. 102–111. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44676086. Accessed 21 Apr. 2021.

“Washington Square Arch.” Park Information. Official Website of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Accessed May 25, 2021. https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/washington-square-park/monuments/1657.

[1] Flint, 67, 69.

[2] Geismar, 11.

[3] Luther H. Harris, Around Washington Square: an Illustrated History of Greenwich Village (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 7-9.

[4] Harris, 10.

[5] Harris, 10.

[6] Ibid, 6.

[7] Ibid, 12.

[8] Ibid, 15.

[9] Harris, 14.

[10] Flint, 67.

[11] Harris, 15.

[12] Ibid, 88.

[13] Flint, 69.

[14] Harris, 18-21.

[15] Ibid, 62-63.

[16] Harris, 54.

[17] Brown, 196.

[18] Harris, 89.

[19] Ibid, 131.

[20] Harris, 74-75.

[21] Ibid, 76.

[22] Flint, 68-69.

[23] Ulam, 104.

[24] Harris, 89.

[25] Flint, 68.

[26] “Washington Square Arch,” Park Information (Official Website of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation), accessed May 25, 2021, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/washington-square-park/monuments/1657.

[27] Brown, 196.

[28] Harris, 75.

[29] Flint, 68-69.

[30] Brown, 197.

[31] Flint, 69.

[32] Harris, 107.

[33] Berthold, 430.

[34] Harris, 131.

[35] Dennis Berthold, “Melville, Garibaldi, and the Medusa of Revolution,” American Literary History 9, no. 3 (1997): pp. 433, http://www.jstor.org/stable/490175.

[36] “Alexander Lyman Holley.”

[37] “ALEXANDER L. HOLLEY.; Interest in Troy in the Proper Site for His Memorial Bust.”

[38] Harris, 22.

[39] Flint, 70-71.

[40] Flint, 72-87.

[41] Ibid, 80.

[42] Emily Kies Folpe, It Happened on Washington Square (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 269.

[43] “Washington Square Memorial Flagstaff,” Park Information (Official Website of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation), accessed May 25, 2021, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/washington-square-park/monuments/1659.

[44] When I first saw it, I mostly really just wanted to touch the sandstone because the red was so bright and the sandstone looked soft, especially in comparison to the cool tones and sharp edges of most glass and steel skyscrapers in the borough. The scale of the giant red cube was mystifying.

[45] Erich Goode, The Taming of New York's Washington Square: a Wild Civility (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 10-11.

[46] Monika Krause, The University against Itself the NYU Strike and the Future of the Academic Workplace (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2008), 23.

[47] Rabinowitz, 49-49.

[48] “Alexander Lyman Holley.” Park Information (Official Website of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation), accessed May 25, 2021, www.nycgovparks.org/parks/washington-square-park/monuments/735.

[49] The statue is now a popular location for skateboarders to experiment and perform tricks with friends.

[50] “Giuseppe Garibaldi,” Park Information (Official Website of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation), accessed May 25, 2021, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/washington-square-park/monuments/571.

[51] Flint, 89-90.

[52] Finn.

[53] Ulam, 102-104.

[54] Ibid, 103.

[55] The recent college admissions scandals as well as the recent illegal partying seen in the park can further support this idea.